The primary concept for the “Dislocated” series is based in a framework of public as well as personal memory. The project draws parallels with a historical narrative associated with the expulsion of the German population from Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia, after World War II, in the place where I grew up. In 1946, my Grandfather Ladislav arrived in a semi-vacant village called Groß Schönau (Velký Šenov in Czech) and acquired a piece of land with a house, which subsequently became a home for three generations of my family. Growing up in the house, I was constantly confronted with fragments of someone else’s past that never stopped seeping into our reality. Miscellaneous ordinary objects left behind by the German family fused with our life.

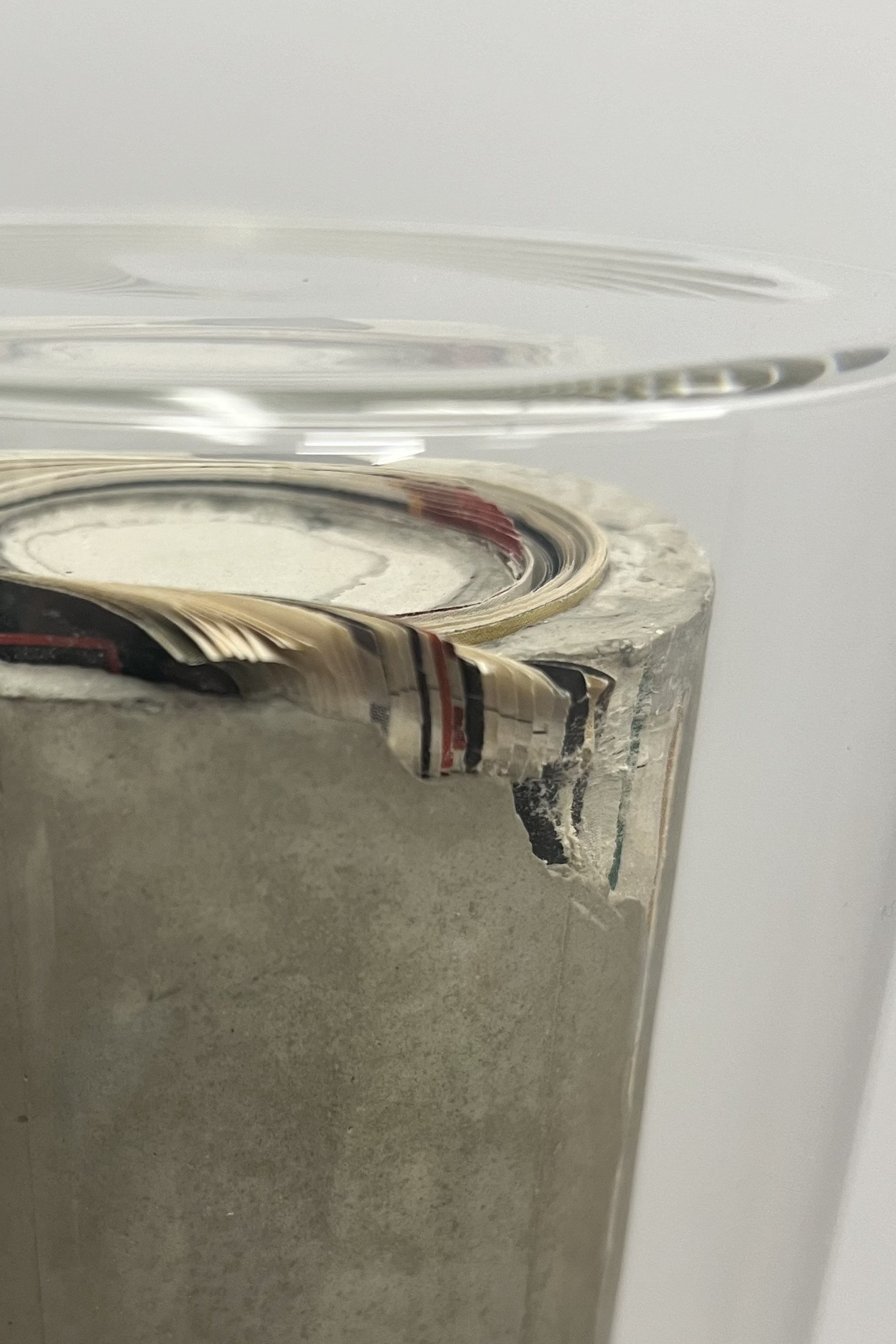

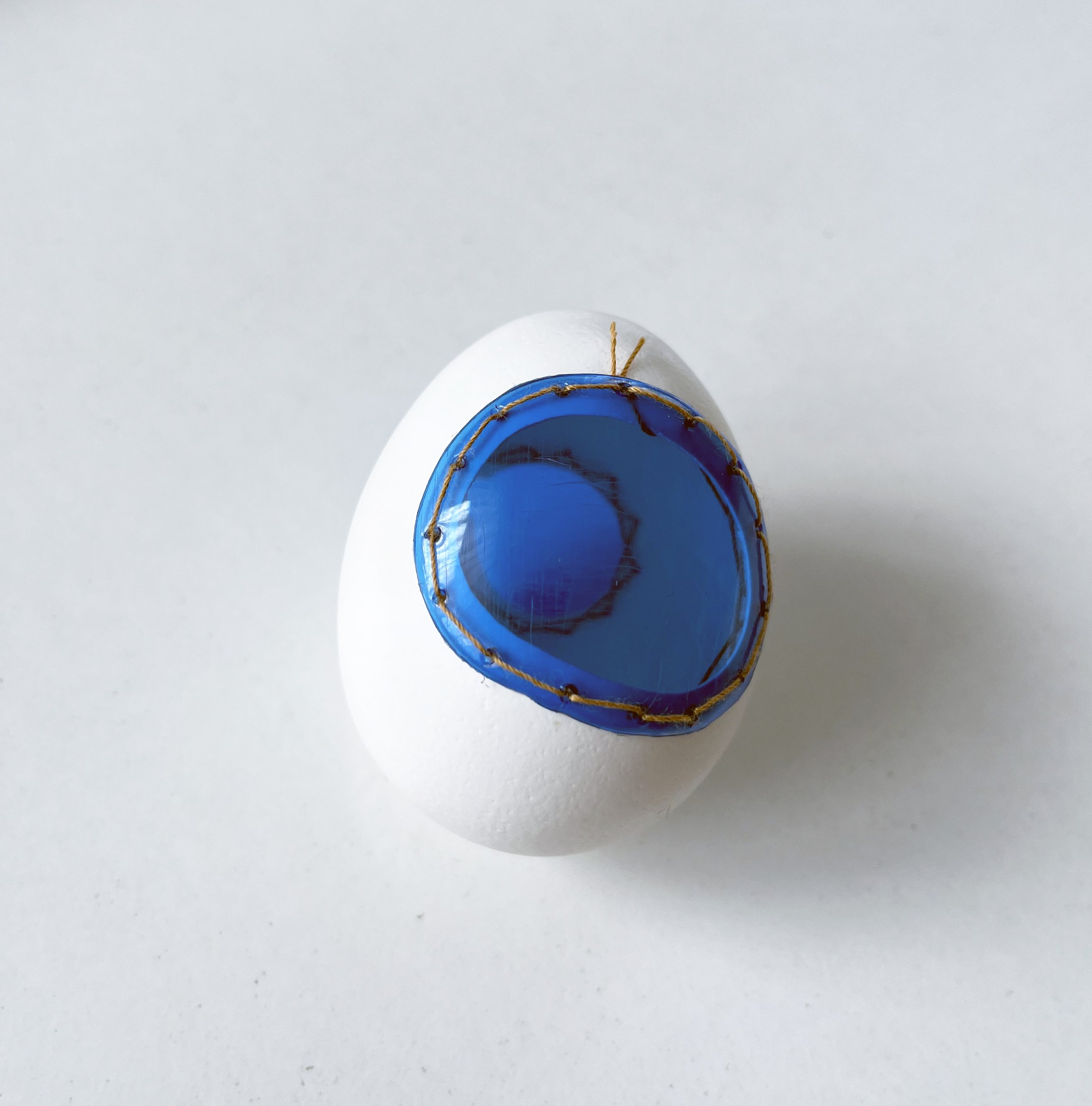

The installation consists of small sculptures constructed from various utilitarian objects for daily use such as silverware, dishes and other kitchen utensils. These objects symbolize the essence of domesticity and the comfort of day-to day routines performed during communal meals; small intimate moments that amount to shared experiences. The familiarity of the objects was altered and their routine function scrambled to the point of uselessness. Reassembled pieces point to the illegibility of recollection resulting in (re)construction of a “surreal” situation using its material extensions filled with symbolic connotations (ritual, tradition, sense of belonging).

As a result of the transformation, the objects gained a new and unexpected meaning. In a paper, Margaret Gibson titled “Death and Transformation of Object and Their Value”, presents an idea that overlays with my point of view. “Objects mediate and produce death discourse just as death mediated and produces value and meaning. The movement of objects within, across and between private/personal spaces and relationships, public spaces and relations, and commercial domain and relations is about value transformation. Value is a fluctuating, comparative or relative measure, and in the sphere of personal life and space objects attain, maintain or transform in both value and meaning through the life course and through events such as loss of home, homeland, migration, war, disaster, death and bereavement.” The definite nature of the intervention into the material simulates the abrupt change in course of events. The choice of materials and their modifications reference the loss of heritage and personal history. The combination of porcelain, sterling silver and concrete generates a contextual contrast; sterling silver refers to lost heirlooms with real monitory value and plain undecorated porcelain serves as a medium for home life overrun by a new circumstance, while unforgiving nature of concrete stands as a metaphor for stillness and unwillingness to change.

The tablecloth covered with concrete in an integral part of the installation. The distressed and organic quality of the surface contrasts with the rigid edges and slickness of objects placed on it. The hard shell reaching all the way to the floor produces an interior cavity inaccessible to the viewer. It refers to a space where “things” are hidden and forgotten, almost like a Schrödinger's box where issues and problems might exist and not exist at the same time. This idea speaks of the silence that the event in our collective history is clothed with.

The Dislocated project is a personal attempt to face and reconcile a troubled historical event, with consequences imprinted onto my family legacy. The work challenges the notion of historical amnesia and the irrefutability and irreversibility of the unresolved political conflict filtered through my experience as someone who is permanently yet voluntarily dis-located from my own homeland.

As we move through life, we create our own historical aura and in doing so we are simultaneously attached to an invisible umbilical cord that connects us to a shared collective past. It is a bond that cannot be severed, even though we might want to deny its existence due to the fact that the “place” we are linked to might be tinted with blood, tragedy and sadness. How do we resolve the inner conflict with history? Is it possible to surrender to a choice of reconciliation instead of letting ourselves to be crushed by the burden of tragedy? I believe we can and it starts with an acknowledgement. I know I want to come to terms with the terrible legacy I carry with me.

Photo 1, 4, 6: David Broda